AI & HOME OFFICE

Our assessment explained

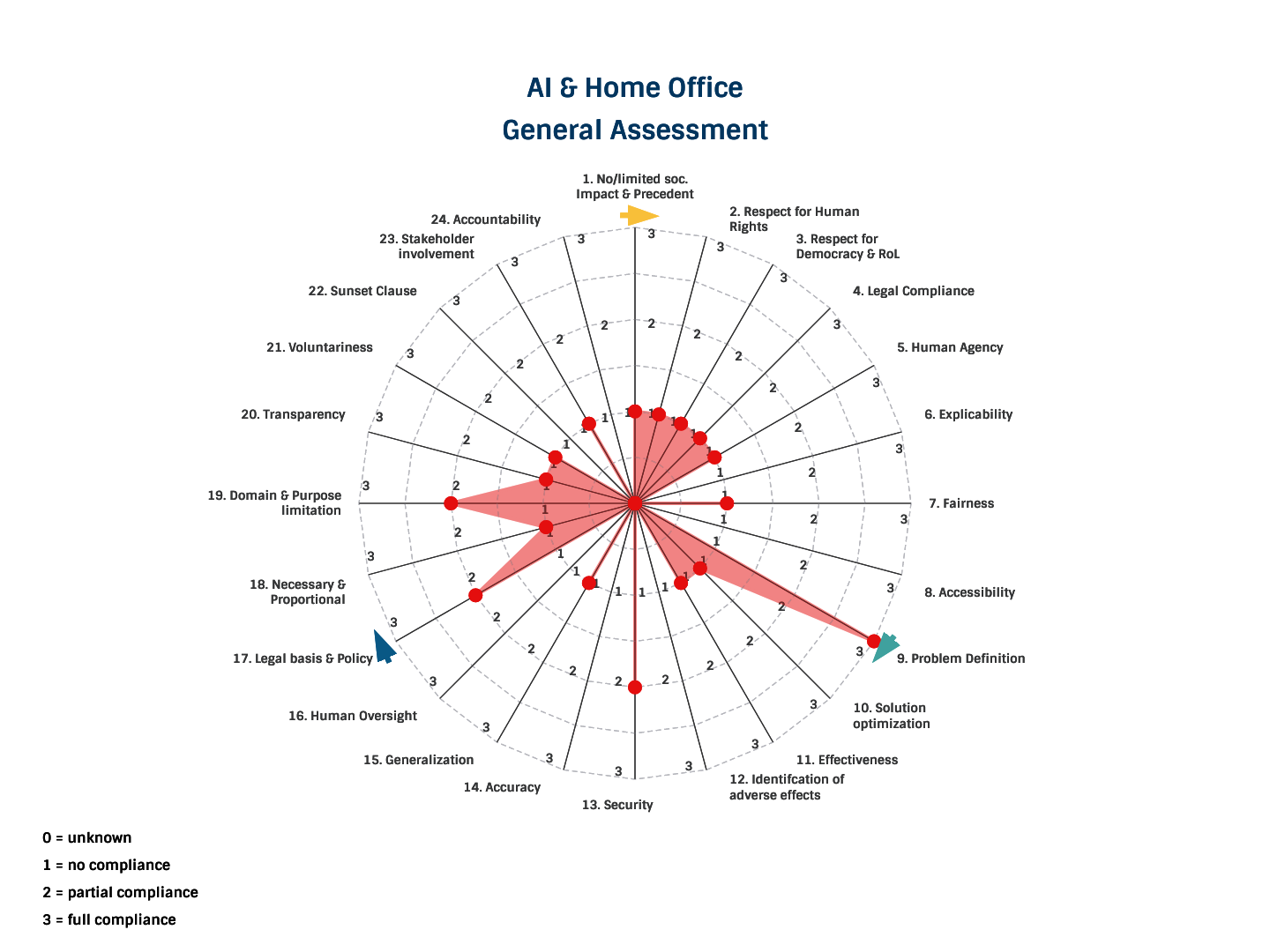

- According to a survey by Gartner, about 10% of business adopted applications for home office monitoring prior to the pandemic. The number has increased to 30% of businesses and is rising.

- Among others, applications such as Office 365 Monitoring, ActivTrak, Timedoctor, Enaibe, Hubstaff, Teramind, StatusToday, Controlio, TeamViewer, CleverControl, Spyrix Employee Monitoring, Kickidler, Veriato, DeskTime, WorkAuditor, Timely, Sneek, SoftActivity are on the market.

- Many of these systems use invasive ‘tracking’ elements such as eye tracking, location tracking, mouse movements, copy and paste behaviour, search behaviour, sound tracking, time tracking, keyboard tracking, etc.

- No extensive research has been done assessing the effectiveness of AI-based monitoring tools compared to non-AI-based approaches that assure employee productivity.

- It is unclear whether specific features of monitoring software actually capture true productivity and performance of employees.

- It is possible to outsmart the software which raises accuracy and fairness concerns.

- Reliable productivity measurements are difficult with more complex and creative positions.

- Home office monitoring has a significant negative impact on citizens and society as the use of ‘real-time’ and ‘always-on’ technology can undermine trust, confidence and well-being, specifically in employment relationships.

- There is significant impact on the human rights to a private life, a safe and healthy workplace and human agency.

- It might set an undesired precedent for the future: more (acceptance) of surveillance.

- There might be national labour laws that require a specific legal basis for worker monitoring. Also collective bargaining agreements could have specific rules for worker monitoring.

- Most of the times, employees are not involved in the decision to apply the system.

- Submission to the application is not voluntary (either because employees are not made aware of the use of the system or they are obliged to consent).

We see no acceptable trade-off in times of crisis, primarily because it is not clear whether monitoring tools have a positive or a negative impact on employee’s productivity and performance. However, enough concerns and “chilling-effects” have been expressed that make the consideration of less intrusive techniques indispensable. Policies to support the transition to more widespread remote work will need to carefully consider the potential benefits and costs for productivity, job quality, and workers’ work-life balance and mental health. This is especially important in view of rising demand and development of home office monitoring systems, that will likely not be scaled back after the end of pandemic.