ALGORITHMIC GRADING

ALGORITHMIC GRADING

- Algorithmic grading has been replacing International Baccalaureate (IB) final examinations in 2020

- For IB, over 200,000 students from over 3000 schools worldwide were graded using an algorithm

- Algorithmic grading has been replacing A-level examinations in the United Kingdom in 2020

- For A-levels, over 800,000 students were graded using an algorithm

- Full scope of use at national levels or for other curricula is difficult to establish

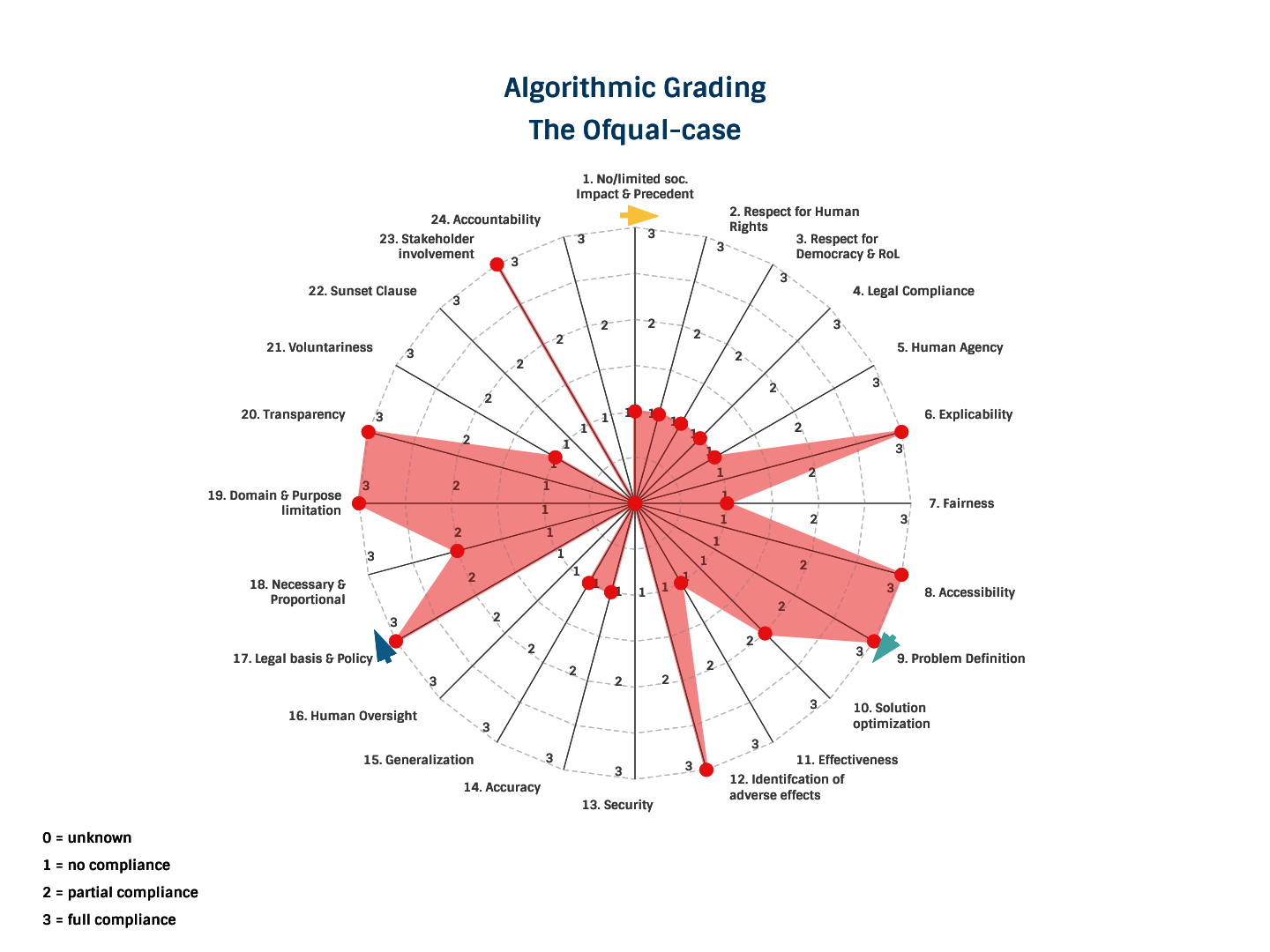

- Predicting grades accurately and justly for every single student is per definition counter-factual and therefore nearly impossible task

- The algorithmic models are set to predict the likely distribution of grades, not assessing the performance of a student on his/her own merits

- In the test-phase, where the results of the algorithm were compared with actual grades, the accuracy of the model used for the “A-levels algorithm” was low – in the range of 50 – 60%

- Unjust or incorrect grading has detrimental effects on the life opportunities of students as they determine their future education/career

- AI algorithm considered past success of the school as a variable, favoured better (and usually private) schools over less successful (usually public) schools, risking deepening inequalities

- Generalizing grading by taking into account variables beyond the student’s own merits.

- Submission to algorithmic grading in the domain of education is usually not voluntary

- For the evaluated case, the deployment of algorithmic grading took place with involvement of key stakeholders such as teachers, students, student’s parents

- For the evaluated case, a vast governance structure was set up

Despite the inability to hold on-premises examinations due to the Corona-crisis and the obvious wish to have as many students as possible have their exams other options could have been examined and used. For example by looking at student’s past work, teacher evaluation, or introduction of alternative assessment methods (take-home exams). Algorithmic grading justifiably inflicts a sense of arbitrariness and injustice in grading. We see no acceptable trade-offs, in particular because of the low accuracy of the system, the impact on the law and several human rights.